Methodology of toolbox for mobilising and redirecting private finance for the green transition

Introduction

The transition to a sustainable economy is both urgent and challenging. The European Union has set ambitious climate goals, including climate neutrality by 2050 and major greenhouse gas reductions by 2030 and 2040. Achieving these targets requires large investments, with the European Commission estimating an annual green investment gap of additional €620 billion (European Commission, 2023). A substantial share of this gap must be filled by the private sector, which will be essential for driving the necessary transition (Andersson et al., 2025). However, fossil investments continue at a large scale and only 1% of European financial market investments are classified as ‘green’ under the EU taxonomy (Alessi et al., 2021). Private sector actors stress that policymakers must set the right conditions to enable and incentivise green investments. Effective public policy is crucial, but choosing the right policy tools requires a clear understanding of the specific investment barriers that need to be addressed.

Context

The public debate on mobilising and redirecting private finance for the green transition often centres on access to capital and financial regulation, as illustrated by the prominent discussions surrounding the EU’s Capital Markets Union (CMU). While crucial, these factors overlook two major challenges. First, investment decisions face broader obstacles, including financial profitability concerns such as operational costs and demand uncertainty, as well as real-economy constraints like labour shortages and administrative inefficiencies. Second, deeper-rooted barriers — such as power imbalances and embedded mental models — further hinder progress. This policy toolbox bridges these gaps by offering a comprehensive set of policy tools to address both explicit and deeper-rooted investment barriers. By adopting a systemic and holistic approach, the policy toolbox provides policymakers, researchers, and decision-makers in the real economy the necessary tools to address specific investment challenges. It also inspires action to overcome barriers within their institutions, ensuring both short-term impact and long-term economic transformation.

Methodology

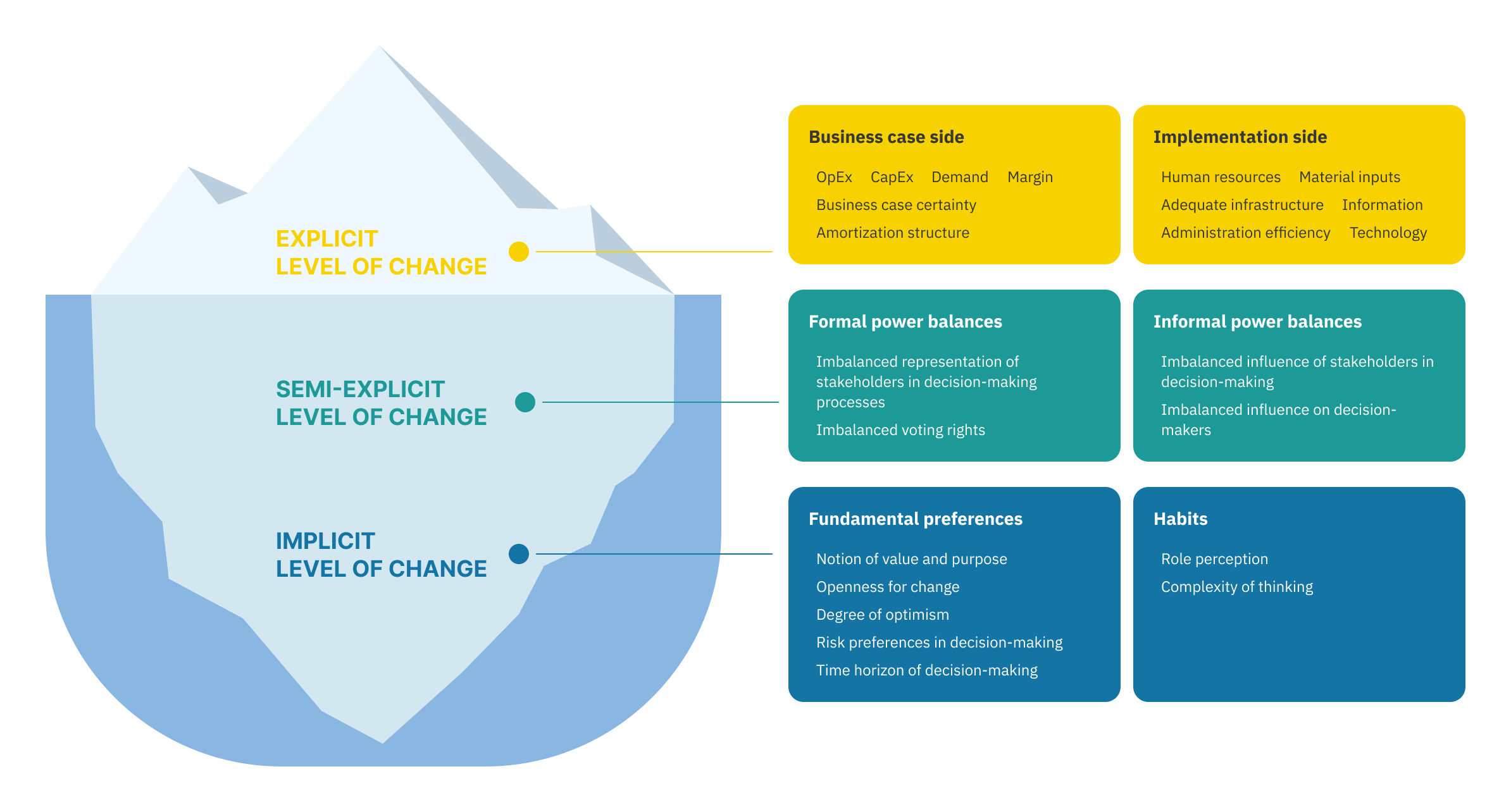

Systemic change in the broadest sense is about ‘shifting the conditions that are holding the problem in place’ (Kania et al., 2018). It necessitates a holistic approach that aligns policymakers, citizens, businesses, and financial actors towards a sustainable economy (Miller et al., 2021). It addresses not just surface-level symptoms of economic issues but also their root causes. Systemic change unfolds across multiple levels (Birney, 2021; Meadows, 1999). Building on various strands of systems literature and frameworks — including The Waters of System Change (Kania et al., 2018) and Places to Intervene in a System (Meadows, 1999) — an adaptation of the Iceberg Model is used to conceptualise three levels of change: explicit, semi-explicit, and implicit. This framework addresses both tangible economic investment barriers and deeper-rooted challenges, such as power dynamics and underlying mental models. The adaptation of existing models places a strong emphasis on investment decisions.

Levels of Systemic Change

1. Explicit Level: This level involves policy instruments that address tangible investment barriers for investors. Within the explicit level, we differentiate between two core aspects that influence the investment process: the business case side and the implementation side. Importantly, all barriers are considered in terms of their relative impact on green compared to fossil investments. This means that policies can be effective not only by reducing barriers for green investments but also by increasing barriers for fossil investments (e.g., through higher OpEx).

Business case side:This side focuses on the economic viability of an investment.

- CapEx: Initial capital expenditures for long-term assets such as buildings, machinery and equipment, which contribute to the foundation of business operations and play a key role in determining overall profitability.

- OpEx: Ongoing operational expenses required to maintain daily business activities, serving as an important measure for profitability.

- Demand: Market need or customer interest in a product or service as crucial measure for profitability.

- Margin: The difference between the selling price and the unit cost of a single product, serving as a key indicator of its profitability.

- Business case certainty: The level of predictability and reduced risk regarding key investment factors, such as CapEx, OpEx, demand, and margin, which influence the viability and success of a business investment.

- Amortisation structure: Temporal structure of expenses and income, determining when the investment will be profitable.

Implementation side: The existence of a business case by itself is insufficient for investments to proceed. In addition, the right real-economy resources and preconditions need to be in place for an investment to be successfully implemented.

- Human resources: Availability and access to the right personnel required to execute business operations.

- Technology: Availability of tools, systems, and technical capabilities to support business processes.

- Material inputs: Access to raw materials or other natural resources needed for production or service delivery.

- Information: Availability of robust information about all relevant aspects of the investment, for instance the socio-ecological impact of investments, or the consumer demand for sustainable options..

- Administrative efficiency: Level of effort required to comply with regulatory requirements for the investment, including paperwork, reporting, and other administrative tasks.

- Adequate infrastructure: Availability of physical, digital and knowledge systems that are required for the successful implementation of business operations, ranging from roads and bridges over software to innovation ecosystems.

- Economic and political stability: Ensuring a stable economic and political environment that provides investors with confidence and long-term planning certainty. This obstacle is included in our methodology for comprehensiveness, as it represents a significant investment barrier. However, it is not integrated into the web application’s filters, as its broad nature—encompassing framework conditions like democracy building—does not align with the granularity of our policy tools, which focus on directly mobilising and redirecting capital.

2. Semi-Explicit Level: This level refers to power dynamics within the system, defined as the distribution and control of power, authority, and influence. These dynamics involve both formal and informal mechanisms that shape decision-making processes among individuals, groups, and organisations (Jess et al., 2023; Kania et al., 2018; Ison, Straw, 2020).

Formal power imbalances, where unequal representation and decision-making rights result in a disproportionate concentration of influence within decision-making bodies across organisations and policymaking.

- Imbalanced representation of stakeholders in decision-making processes: Certain groups or perspectives are underrepresented or excluded, limiting the diversity of interests reflected within organisations or policymaking bodies.

- Imbalanced voting rights in decision-making processes: Decision-making power is unequally distributed, whether in corporate governance structures or policy settings, limiting the influence of certain stakeholders in shaping outcomes.

Informal power imbalances: Refers to unequal access to information and differing levels of influence over decision-makers.

- Imbalanced access of decision-makers to information, which creates disparities in the ability of different actors to make informed decisions, leaving some stakeholders at a disadvantage in the decision-making process.

- Imbalanced influence on decision-makers, where external influence distorts decision-making to serve their own interests (e.g. through lobbyism, market power and concentration, socioeconomic inequalities, or unbalanced opinion leadership).

3. Implicit Level: This level addresses mental models, the underlying beliefs, assumptions, and worldviews of key actors in the system. Policies influencing this level drive long-term changes by reshaping how decision-makers think about green investments. We differentiate between two levels of implicit barriers: Fundamental Preferences and Habits (Jess et al., 2023; Kania et al., 2018; van den Broek et al., 2024).

Fundamental Preferences: These are deeply ingrained beliefs and assumptions held by decision-makers that shape how they perceive problems and solutions. Often unchallenged, these preferences influence decision-making by establishing what is seen as feasible, acceptable, or appropriate, thereby guiding the course of action. Key aspects include:

- Notion of Value and Purpose: The underlying belief about what is worth pursuing, whether driven by financial returns, societal well-being, or long-term sustainability.

- Time horizon of decision-making: Decision-makers may undervalue future benefits, leading to a preference for short-term gains and neglecting long-term systemic changes.

- Risk preferences in decision-making: These refer to the attitudes and tendencies of decision-makers toward uncertainty and potential outcomes. They reflect how much risk an individual or organisation is willing to accept in pursuit of a desired goal, influencing decisions on investments.

- Openness for change: The willingness to challenge existing paradigms, reconsider entrenched assumptions, and adapt to evolving circumstances.

- Degree of optimism: The prevailing outlook on the future, reflecting whether decision-makers tend to expect the future to bring more opportunities than threats.

Habits: Habits are learned patterns of thought and action that, while more flexible than deeply held beliefs, shape daily decision-making and reinforce systemic inertia or change.

- Role perception: Implicit beliefs about who holds power, who drives change, and who is responsible for action within a system, including actors’ assumptions about their own roles.

- Complexity of thinking (assumptions about how systems function): The way in which actors process information, ranging, for example, from linear, cause-effect reasoning to nonlinear pattern recognition. Similarly, some actors might think in fragmented ways, focusing on isolated parts, while others use systems thinking to see the bigger picture.

Research Design

How were the investment barriers identified?

The methodology builds upon a multi-step approach integrating previous research, expert interviews and desk-based research to identify and analyse investment barriers to the green transition across the three levels of change. The research followed an inductive approach and was continuously refined, integrating ongoing feedback from experts and insights from literature.

Foundation and expansion of research analysis: The research built upon a previous study on the phasing out of gas in industry and buildings in Germany (Energy Independence Council 2024), which included a literature review and a large number of expert interviews from policy, associations, trade unions, civil society organizations, and businesses. To avoid regional and sector-specific bias, the analysis integrated additional survey data.

Exploration of survey data: The analysis examines firms' perceptions of investment barriers through reports and surveys from institutions like the European Investment Bank (EIB), European Central Bank (ECB), ifo Institute, KfW, and Bundesbank’s Online Panel for Firms (BOP-F). To avoid biases, additional surveys, including the EU-wide EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS), are integrated to ensure a comprehensive representation across regions, company sizes, and sectors. The survey and report data confirm an important caveat: they primarily reflect explicit investment barriers that firms encounter in their day-to-day operations. At this explicit level, the policy toolbox conceptualises thirteen investment barriers that reflect the economic viability of an investment as well as the real-economy resources and preconditions that need to be in place.

Supplementary literature: To address this gap, the policy toolbox integrates previous research such as the ZOE Institutes Methodological overview of the Recovery Index for Transformative Change (RITC), additional literature and expert insights on systemic change, enabling the analysis to extend to the semi-explicit and implicit levels of transformation. This approach leads to the identification of four investment barriers related to power dynamics and seven investment barriers linked to mental models.

How were the policy tools identified?

Building upon the identified investment barriers, the policy toolbox adopted a multi-step approach to identify policy tools capable of addressing these challenges. This process involved a review of existing datasets and policy trackers, supplemented by a literature review and interviews with stakeholders. The process was driven by an inductive research methodology, which was both keyword-driven and iterative, progressively narrowing the focus to uncover specific policy tools to mobilise and redirect private investment for the green transition (Annex Table 1). Given the large number of policies, many of which share a similar underlying logic, they were clustered into broader categories. For instance, various subsidy schemes were grouped into themes such as subsidies for consumption and subsidies for investment.

Exploration of datasets: The initial phase of the research focused on reviewing existing datasets and policy trackers. Keywords such as ‘policy instruments/tools,’ ‘mobilise/redirect private investment,’ ‘green transition’, ‘industrial policy’, ‘policy tracker’, ‘dataset’ were used to explore a range of datasets and policy tracking systems, including for instance the New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO), the SV policy tracker, and the Climate Policy Database. The analysis revealed that existing datasets were either thematically limited, focused on specific policies rather than the underlying tools, or not systemic in nature, underscoring the need for a more comprehensive approach. Despite these limitations, these initial datasets were instrumental in generating an early-stage list of potential policy tools, which was further refined in later stages of the research.

Supplementary literature and expert interviews: To complement the dataset review, the research was expanded through a more in-depth literature review. This stage involved a comprehensive search using internet search engines, focusing on reports from international organisations, academic literature, and publications from think tanks. The review process progressively narrowed the search results by first refining keywords based on the methodological approach, integrating terminology reflecting the three levels of change such as 'decision-making processes', 'fundamental preferences', 'power imbalances', and 'habits'. Keywords were then further refined to address the specific investment barriers, such as 'OpEx', 'stakeholder representation', 'systemic thinking' (Annex Table 1). Additionally, by examining both existing and proposed policy tools, the literature review provided further context, offering the web application user empirically grounded examples to enhance their understanding. Validation of the findings was carried out through interviews with stakeholders. These interviews provided valuable qualitative data, ensuring that the research remained grounded in both theoretical frameworks and real-world practices. Stakeholder feedback played a crucial role in confirming the relevance of identified policy tools and in refining the understanding of investment barriers.

Refining keywords & Mapping policy tools: Throughout the research process, the keywords used to guide the search were continuously refined and adapted based on ongoing findings (Annex Table 1). This iterative keyword-driven approach was essential in narrowing the focus from broader thematic categories to more specific policy tools capable of addressing specific investment barriers. The final stage marked a synthesis of all data and insights collected from datasets, literature, and interviews, leading to a comprehensive list of policy tools which were matched with the specific investment barriers.

Application of methodology

To navigate the policy toolbox effectively, users can apply a range of filters that help structure and refine their search based on key characteristics of policy instruments. These filters allow for a more targeted exploration of relevant tools and their role in addressing investment barriers.

- Policy area: Applying this filter, the user can explore policy instruments across policy areas, including public (co)-funding, taxation, monetary policy, trade policy, competition policy, labour markets and education, financial and non-financial regulation, and information and coordination.

- Policy status: This filter allows users to distinguish between instruments that are already implemented in an EU member state, at the EU level, or outside the EU, as well as those not yet implemented.

- Affected entity: Using this filter, the user can identify which entities — such as companies, commercial banks, households, state actors, central banks and financial regulators, development banks, electricity producers, unions, or credit rating agencies — are directly affected by a given policy instrument.

- Incentive structure: This filter allows users to explore whether an instrument provides a positive incentive for green investments, acts as a disincentive for harmful activities, or combines both approaches.

- Immediate fiscal effect: Applying this filter, the user can assess whether a policy instrument causes fiscal costs, generates revenues, has no or only administrative costs, or has an uncertain fiscal impact. This assessment is limited to the direct short-term effects of the policy instrument. The indirect long-term effects (like generating economic growth and thereby more tax revenues) are not covered by this filter.

The filter options allow users to get an overview of policy tools, understand their specific characteristics, and link them to investment barriers. However, assessing the feasibility and effectiveness of each tool requires additional context-specific analysis. In the future, the toolbox will be applied to specific case studies to further refine its application.

References

Alessi, L., Battiston, S., Melo, A.S. (2021). Travelling down the green brick road: a status quo assessment of the EU taxonomy,". Macroprudential Bulletin, European Central Bank, vol. 15. Available on

Andersson, M., Ulbrich, P.K., Nerlich, C. (2025). Green investment needs in the EU and their funding. European Central Bank. Economic Bulletin Issue 1, 2025. Available on https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/html/eb202501.en.html

Birney, A. (2021). How do we know where there is potential to intervene and leverage impact in a changing system? The practitioners perspective. Sustain Sci 16, 749–765 (2021). Available on https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00956-5

Bundesbank (2025). Bundesbank’s Online Panel for Firms (BOP-F). Available on

Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2024). 2025 Euro Area Report. Available on

https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/2025-euro-area-report_en

Energy Independence Council (2024). Security-oriented Energy Policy – A financing strategy for Germany's independence from natural gas. Available on

European Central Bank (2025). Occasional Paper Series Investing in Europe’s green future Green investment needs, outlook and obstacles to funding the gap. Available on https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op367~16f0cba571.en.pdf

European Commission (2023): Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. 2023 Strategic Foresight Report. Sustainability and people's wellbeing at the heart of Europe's Open Strategic Autonomy. Available on https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52023DC0376

European Investment Bank (2024). EIB investment survey 2024 – European Union overview. Available on https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1862f494-91ae-11ef-a130-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

European Investment Bank (2024). Investment report 2023/2024 – Transforming for competitiveness. Available on

European Investment Bank (2025). EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS). Available on

https://www.eib.org/en/publications-research/economics/surveys-data/eibis/

Evenett, Simon, Adam Jakubik, Fernando Martín & Michele Ruta (2024). The Return of Industrial Policy in Data. NIPO dataset. Available on https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/12/23/The-Return-of-Industrial-Policy-in-Data-542828

Ison, R., Straw, E. (2020). The Hidden Power of Systems Thinking: Governance in a Climate Emergency (1st ed.). Routledge.

Jess, T., Blom, P., Dixson-Declève, S. (2023). From financing change to changing finance. Available on

Kania, J., Kramer, M., Senge, P. (2018). The Water of Systems Change. FSG. Available on

https://www.fsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Water-of-Systems-Change_rc.pdf

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points-places to intervene in a system.

Miller, C. and Davies, W., Barth, J., Hafele, J., Dirth, E., Korinek, L., Schulze, N., Kögel, N., Kiberd, E. (2021): Methodology for Recovery Index of Transformative Change (RITC). ZOE Institute for Future-fit Economies. Cologne. Available on

https://zoe-institut.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Methodology-brief_VFinal-1.pdf

NewClimate Institute, Wageningen University and Research & PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (2016). Climate Policy Database. Available on DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7774109

Scheuermeyer, P. (KfW) (2025). Investitionsentwicklung in Deutschland – eine Bestandsaufnahme. Available on

Sustainable Views (2025). Policy Tracker. Available on https://www.sustainableviews.com/policy-tracker/

van den Broek, K.L., Negro, S.O., Hekkert, M.P. (2024). Mapping mental models in sustainability transitions. Available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2024.100855

von Maltzan, A.; Zarges, L. (ifo Institute) (2024). Der Investitionsstandort Deutschland aus Unternehmenssicht. Available on https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/sd-2024-03-vmaltzan-zarges-investitionsstandort-deutschland-familiendatenbank.pdf

Annex

Table 1: Inductive Categorisation of Keywords Across Analytical Layers

| Layer | Description | Keywords/Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Stage | Identification and review of broad datasets and policy trackers relevant to how policy instruments mobilise private investment for the green transition. | Climate policy tools, database, green finance, green investments, industrial policy, investment mobilisation, mobilising/redirecting private finance, policy instruments, policy tracker, transition finance. |

| 2nd Stage | Refinement of keywords based on methodological approaches, integrating levels of change and broad thematic categories. | Decision-making processes, fundamental preferences, formal power imbalances, habits of thought, informal power imbalances, investment decisions, mental models, power dynamics, systemic change. |

| 3rd Stage | Refinement of keywords based on previous layers, with a focus on investment barriers at different levels of change. | Amortisation structure, adequate infrastructure, business case certainty, CapEx, complexity of thinking, corporate governance, degree of optimism, demand, economic and political stability, human resources, imbalanced access to information, imbalanced influence on decision-makers, imbalanced representation of stakeholders, imbalanced voting rights, information, margin, material inputs, notion of value and purpose, OpEx, role perception, risk preferences, stakeholder representation, systemic thinking, technology, time horizon of decision-making. |

| 4th Stage | Identification of additional policy tools based on a refined keyword search, focusing on variations of investment barriers. | Fragmented thinking, hierarchies, imbalanced opinion leadership, innovation aversion, intertemporal utility discount rate preferences, linear progression assumption, lobbyism, long-term thinking, market power and concentration, resistance to transformation, risk aversion, shareholder-value mentality, short-term thinking, socio-economic inequalities, status quo bias, techno-optimism bias. |